WWHP Newsletter Vol. 1, No. 10, Fall 2000

In Celebration of Women 2000 Art Honoring Women

American Woman

ArtsWorcester honors the spirit of the American woman with the exhibition Our Image, Ourselves. On view at ArtsWorcester, October 19 through November, 4, 2000, this exhibit coincides with Women 2000. Images of women of all ages in different states of life are presented in a variety of media. The opening reception is Thursday, October 19, from 6–8 p.m. The new ArtsWorcester Gallery is located at The Aurora, 660 Main Street in Worcester.

Heritage on exhibit

The exhibit Reclaiming Our Heritage: Worcester Women’s History, 1850, was created by Carolyn Howe, President of WWHP, and seven students at Holy Cross College. The exhibit features the first National Woman’s Rights Convention, other reform movements, and life in Worcester in 1850. It will be shown at the YWCA until October 1; at City Hall on October 2; at the Unitarian Universalist Church on Holden Street, October 14–15; and at Mechanics Hall October 20–22. The exhibit is also available to travel. If anyone wants it for display, please call Carolyn Howe at 793-3478.

Insight from the Eastman Collection

Stage of Brinley Hall

The Worcester Art Museum will contribute to Women 2000 by presenting the exhibition Insight: Women’s Photographs from the George Eastman House, a selection of works from one of America’s premier photography collections that celebrates the remarkable achievements of women photographers since 1850.

A selection of fifty-five works will emphasize the diversity and richness of women’s approaches to the photographic medium. The works were chosen to reflect the personal vision of each artist. As a group, they articulate the breadth of women’s experience; they confront clichés and social expectations. Landscape, portraiture, and genre subjects will be presented, along with documentary and photojournalistic work. While some of the photographs in the exhibition represent stylish fantasy, others depict, allegory and reflect on issues of aging, sexuality, and self-definition.

Among the artists represented in this exhibition will be the nineteenth-century pioneers Julia Margaret Cameron, Genviève-Elisabeth Disdèri, and Gertrude Käsebier, as well as such twentieth-century artists as Anne Bridgman, Margaret Bourke-White, Jan Groover, and Carrie Mae Weems.

This exhibition was organized by the George Eastman House, in Rochester, New York. It will be on view in the first-floor gallery of the Frances L. Hiatt wing at the Worcester Art Museum from September 16 through November 26, 2000.

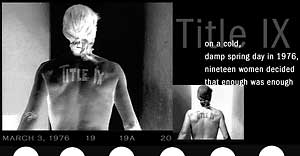

Sneak Preview, Women 2000: A Hero For Daisy

This moving portrait of Yale rowing legend, Chris Ernst, will be shown at the Worcester Centrum Centre, Saturday, October 21st at 8:30 a.m. as part of Women 2000. Filmmaker Mary Mazzio will appear at the screening and be available for discussion and questions.

This moving portrait of Yale rowing legend, Chris Ernst, will be shown at the Worcester Centrum Centre, Saturday, October 21st at 8:30 a.m. as part of Women 2000. Filmmaker Mary Mazzio will appear at the screening and be available for discussion and questions.

In 1976, Ernst galvanized her rowing team to storm the Yale athletic director’s office to protest the lack of locker-room facilities for women. In front of a reporter from The New York Times, the women stripped, exposing 19 sets of breasts emblazoned with the phrase “Title IX” in blue marker (Title IX refers to legislation enacted in 1972 that mandated gender equity for all institutions receiving federal aid). The story was carried by all of the major international news outlets, and Ernst won her fight for new locker rooms two weeks later. She went on to represent the U.S. in two Olympic games, becoming a world champion in 1986. The film includes interviews with Ernst, who is now a plumber; Yale graduate Senator John Kerry; legendary football coach and former Yale athletic director Carm Cozza; and David Vogel, the president of the U.S. Rowing Association and Yale’s head rowing coach.

Writer/Director/Executive Producer Mary Mazzio, a partner with the law firm of Brown, Rudnick, Freed & Gesmer in Boston, was herself a member of several national teams including the 1992 Olympic Rowing Team. A close personal friend of Chris Ernst, Mary has relationships with and access to the community of people involved in this project. Mary, a product of Boston University’s graduate film productions program, is a graduate of Mount Holyoke College and Georgetown Law School. A recipient of numerous awards including the Henry Luce Foundation’s Fellowship (to Korea) and the Rotary Foundation Graduate Fellowship (to France), Mary has served on a number of Boards of Directors including Shackleton Schools, Sojourner House (a homeless shelter), and The Greater Boston Symphony Orchestra.

In Search of Props

Do you have any of the following items around the house, or do you have connections with an antique dealer/museum who might extend a loan to WWHP? These items are needed for the play Angels & Infidels October 20–22 at Mechanics Hall:

- Fake tomato

- Mid-19th century clothes rack

- Mid-19th century table with 3 straight back chairs

- Carpetbag

- Mid-19th century rocker

- Mid-19th century small table

- Hurricane/oil lamp

- Mid-19th century framed photograph

- Mid-19th century cash register and $34 period currency

- Hurdy Gurdy

- Bouquet of mums (real or good quality silk)

- 2 wooden crates to stand on

- 6 more Mid-19th century straight back chairs (some matching)

- Gavel

- 30 state American flag on stand

- Mid-19th century water pitcher

- 2 clear plastic water glasses

- Reproductions of Boston Daily Mail, NY Herald, and NY Tribune

- 3 Mid-19th century wooden stools

- 2 period coffee mugs

- 3 period teacups and 2 saucers

- Cloth sack of books of Narrative of Sojourner Truth

Please call or e-mail Karen (nlm@burbankeducators.com) if you have any of these items.

An Oxford Woman

The historical character I have chosen to portray in the play Angels and Infidels is Emily Sanford of Oxford, Massachusetts. I chose to portray her for two reasons: we share the same first name and the same hometown.

I began researching Emily’s life at the Worcester Public Library. The 1850 Massachusetts census showed that Emily was twenty-eight years old and lived in Oxford with her husband James Sanford and several members of his family, including his sister Hannah Sanford, who also attended the 1850 convention in Worcester. Emily lived at 302 Main Street, where the CVS pharmacy stands today.

A history of the town of Oxford gave me some information on Emily’s husband James. He was a trader and businessman in the town of Oxford. From 1838 to 1841 he was a licensed retailer of “spirits” at his North Oxford store. James served as assessor for the town of Oxford and postmaster for the town of Charlton.

A search through the Charlton vital records gave me some background information on Emily. She was born December 3, 1821, the daughter of John and Sally (Davis) Spurr. Her father was a notable Charlton resident and was involved in the incorporation of the Charlton Cotton, Woolen, and Linen Association. Her mother was a descendent of Ebenezar Learned, a general in the Revolutionary War and a prominent Oxford resident. Emily had one older sister and three older brothers, one of whom died at sea when he was only seventeen years old. Emily’s mother died in 1831, after which her father remarried.

As is often the case when researching nineteenth-century women, I have found very little personal information about Emily. I am still searching for information on her schooling and religious affiliation.

Emily died childless in Oxford on May 31, 1887, at the age of sixty-five. Her cause of death was listed as “exhaustion.” According to the Oxford vital records she is buried in Oxford, but I have been unable to locate her grave.

Now Showing

Walk or drive by 484 Main Street (the Denholm Building) and, see in the far-right window, a WWHP display about Women 2000, including T-shirt, bumper stickers, buttons, banner and brochures, and the beautiful historical mini-panels produced by Carolyn Howe’s Holy Cross students. The display is up through the end of October through the courtesy of Assumption College and its “Open Windows to Arts and Culture.”

Walking Tour

The Markers and Monuments and Heritage Trail Committee sponsored a Downtown Walking Tour of Women’s History on Saturday, July 29. The tour began and ended outside Mechanics Hall in Worcester.

Led by Carol Kozlowski, a docent for Preservation Worcester and the Worcester Historical Museum, the tour focussed on women’s contributions to Worcester’s early history; the lives of working women in Worcester, especially in the nineteenth century; the role that Worcester women played in the struggle for the abolition of slavery, the struggle for female suffrage, and other social movements; and the homes, workplaces, meeting halls, and other buildings associated with these women.

Highlights of the walking tour included a visit to the Worcester Historical Museum, a reception at the historic home and office owned by Patricia Jones of P. L. Jones and Associates, and a private tour of the Paul Revere Room at the Unum Provident Company.

Attendees also received information on and directions to the homes and haunts of other important women in Worcester and its environs.

The tour attracted more than three dozen participants and even earned a profit. Its success was the result of hard work by Dotty Goldsberry, Laura Howie, and Carol Kozlowski of the Markers and Monuments Committee, and Beth Sweeney of the Marketing Committee, as well as the kindness and generosity of the Worcester Historical Museum, Preservation Worcester, P. L. Jones and Associates, and Unum Provident.

Stitching History

On the evening of Thursday, August 3, more than a hundred people came to the Worcester Historical Museum to attend a quilt exhibit and lecture on quilting that was sponsored by the WWHP.

The evening began with a display of several dozen antique, vintage, and contemporary quilts, including a recently completed quilt, on loan from the Worcester Senior Center, which displays the history of the city of Worcester; a showing of the prizewinning film Hearts and Hands: The Influence of Women and Quilting on American Society; and a raffle for three baskets of fabric and quilting materials—an honorable mention prize, a first prize, and a grand prize.

The highlight of the evening was a wonderful lecture by Jennifer Gilbert, curator of the New England Quilt Museum in Lowell. This lecture, entitled “Quilts and the Stories They Tell,” juxtaposed images of historical and contemporary quilts in order to illustrate the continuing relationship between quilting and the history of social reform in America. Afterwards, Ms. Gilbert conducted an amazing ad hoc analysis, of about 20 quilts that individuals had brought with them.

This event was a tremendous success, judging by the large number of people who came to it on a rainy night and the positive feedback that they gave afterwards.

The Marketing Committee, who sponsored this event, had hoped to reach out to an audience interested in quilting and other historical crafts associated with women but perhaps unfamiliar to WWHP. We were pleased, therefore, that the raffle, for which members of the WWHP were ineligible, yielded more than 75 new names and addresses for our database.

Quilts: American Women Stitching History was organized by Beth Sweeney, with generous assistance by Nancy Ford, Laura Howie, Heidi Paluk, Julie Parent, Linda Rosenlund, and Katie Worrick, all members of the Marketing Committee. The Committee wishes to thank the Worcester Historical Museum, which co-sponsored the event; Creations in Cloth, the Worcester Senior Center, and a host of individuals who loaned their quilts for the show, especially Christine Astley, Rita Knox Baker, Joan Bedard, Jessie and Dale Fair, Nancy Ford, Guy Jones, Mitzi Nelsen, Deborah Robinson, Donald and Sheila Reid, and Susan Elizabeth Sweeney; and the many businesses that made generous donations for the raffle: Appletree Fabrics, Betsey’s Sewing Connection and Quilt Shop, Calico and Company, Calico Crib, Colonial Crafts, Fabric Place, Gifted Hands, Spencer Frameworks, Tatnuck Booksellers, Worcester Center for Crafts, and Wright’s Factory Outlet.

Kenney Presents

WWHP is pleased to announce the appointment of Brad Kenney as producer of Angels and Infidels. Brad comes to us with extensive work as producer for the Wachusett Theatre Company, known for big-name musical productions throughout Central Massachusetts. He has also produced the summer musical theatre seasons at Foothills Theatre starring celebrities like Eddie Mekka.

Brad has just been named one of the “40 under 40” by Worcester Business Journal. The awardees are the 40 most influential people under the age of 40 in Worcester.

Where to Get Tickets

Tickets for the play Angels and Infidels are available through the Mechanics Hall box office at 752-0888.

Ernestine L. Rose & Paulina Wright Davis: Two Women Who Jump-Started the 19th-Century Women’s Rights Movement

Ernestine L. Rose

Paulina Wright Davis

It was 1836 when Ernestine L. Potowski Rose, a Polish-born rabbi’s daughter emigrated to the United States from England, settling with her husband, William Ella Rose, in a predominantly immigrant neighborhood of New York City. That same year, Thomas Hertell, a member of the New York State Assembly introduced a bill to give women the right to control their own property after marriage, but the legislation languished for lack of an active constituency.

Influenced by ideas of the Enlightenment, Ernestine had challenged her father’s religious orthodoxy as well as his script for her life. Ernestine was just sixteen when her mother died, leaving her a substantial inheritance. Hoping through marriage to bring Ernestine back within the fold of a more traditional way of life, her father made a contract with a prospective bridegroom in which Ernestine’s inheritance was to be the dowry. Rather than submit to a marriage not of her choosing, Ernestine appealed to a secular court to win back her inheritance, then left Piotrkow for Berlin. Some years later in London, she joined Robert Owen’s socialist movement and developed her political outlook and public speaking skills within its active feminist wing. It was in the Owenite movement that she met William Rose with whom she had a marriage that lasted nearly half a century and appears to have been a genuine partnership of minds and hearts.

The issue raised by Hertell’s legislation resonated deeply with the formative event of Rose’s youth, her appeal for justice and the right to control her own life and property. Rose lost no time involving herself in the political life of her new country, knocking on doors to collect signatures in support of Hertell’s legislation. Yet, public opinion was so unprepared that Rose reported that she obtained only five signatures in her first five months of door-to-door petitioning. Some women maintained, perhaps ironically, that they “had rights enough;” others, fearful of a husband’s anger or ridicule, simply slammed the door in her face. Yet Rose persisted, soon joined by her first colleague Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis, who collected signatures in western New York.

Eventually Rose and Wright Davis were joined by others, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, in the campaign for women’s property rights. A bill was finally passed after Stanton addressed the New York State Assembly (where her father was a member), and presented the petitions. By then, Rose and Wright Davis had been collecting signatures for over a decade and Rose had addressed the New York State Assembly more than ten times. Thus, by 1848, the year of the Seneca Falls Convention, the fledgling women’s rights movement had already gained its first victory, passage of the legislation Rose and Wright Davis had championed over a decade earlier.

We are particularly grateful to Paulina Wright Davis as we approach this 150th anniversary of the first national woman’s rights convention. The 1850 convention might never have happened had Wright Davis not stepped in to help Lucy Stone carry out the mandate of a New England Anti-Slavery Society meeting to call a national convention on women’s rights. Wright Davis used her considerable resources of time, wealth and intelligence to organize, finance, and chair the historic 1850 Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. Ernestine Rose took an active role on the Business Committee, which forged the major resolutions of the Convention and she gave an important speech. Rose continued to play a major role at every subsequent national convention and many state conventions for the next two decades. In addition, Rose fostered international awareness within the 19th-century women’s movement by acting as its translator, rendering letters and speeches from feminists in France and Germany into English at the U.S. women’s conventions.

Wright Davis, born in Bloomfield, New York in 1813, moved west with her parents who pioneered the settlement of the western part of the state. By the age of eleven, she had lost both parents and was subsequently raised by a strictly religious aunt. Through her own explorations of revivalist religion, and later the Swedenborgian movement, Wright Davis discovered a more personally empowering spirituality, and developed an awareness of women’s rights and of her own capabilities.

Wright Davis was married twice; both times to wealthy men who encouraged and shared her interest in reform. Neither husband was willing for her to travel away from home to lecture, but Paulina contributed in significant ways, founding and editing The Una, one of the first women’s rights newsletters in the 1850s, and organizing a Ladies Physiological Society in Providence. After the death of her second husband, Wright Davis studied anatomy and physiology at a medical school in New York City, though she was barred from attending classes with the all-male medical students. Then she took her physiology lectures on the road.

What was it about the character and backgrounds of these two very different women that gave them the vision to initiate political action and the persistence to stick with it before there was an organized movement?

Thanks to her experience in the Owenite movement, Rose was already an accomplished speaker when she arrived in the U.S. in 1836, a time when speaking in public was considered a somewhat scandalous avocation for a woman. It was also a risky one for anyone, man or woman, who espoused an unpopular cause. Speakers were routinely heckled and sometimes even threatened by mobs. But Rose was firmly dedicated to her mission of inspiring Americans to extend the ideals of our Declaration of Independence to include blacks and women. Rose traveled throughout the Northeast, the Great Lakes region, and even the border states of the South, lecturing on abolition, women’s rights, and other reforms, courageously standing up to “respectable” bigots and rowdy mobs. By the mid-1850s, Rose was known as “The Queen of the Platform,” celebrated for the logic, humor, and fervor of her presentations.

Despite their key role in initiating action on women’s rights, both women were controversial within the movement they originated. Rose as an immigrant, a socialist, and atheist of Jewish background, was unacceptable to those reformers who wished to emphasize the movement’s American roots and Protestant-influenced ideology. Her inclusion was championed by Stanton, Anthony, and others who wanted the women’s movement to represent all women irrespective of creed, and who respected Rose’s initiative and commitment. Wright Davis brought the glamour of an elegant society woman to the movement. Praised by some for demonstrating that women’s rights reformers could be attractively fashionable, Wright Davis was criticized by others for over-dressing in a style that might be off-putting to the working class women the movement had yet to reach. Yet, these two women, so different in background and personal style joined forces to act on behalf of all women.

Were Rose and Wright Davis friends as well as colleagues? Unfortunately, Rose rarely wrote personal letters and her papers have been lost. Wright Davis’ papers are at Vassar College and the Rhode Island Historical Society, but do not extend back to this early period of their collaboration, so I can only speculate. Clearly these two respected one another intellectually and politically; and worked well together. Wright Davis wrote glowing praise of Rose’s speeches in her newspaper, The Una. Yet, differences in style, belief, and social class might have been a barrier to personal friendship. Rose was an atheist and materialist; Wright Davis, a believer in spiritualism. Wright Davis with each of her husbands had a large, comfortable home in which to entertain friends and colleagues; Rose and her husband lived in a rooming house over their shop in New York City. Rose was outspoken on behalf of her principles, and did not hesitate to skewer her opponents, and sometimes even her allies, when she disagreed with them. Wright Davis always opened her talks acknowledging the beliefs and conventions of the times, then “disarmed her opponents with her graceful audacity.”

Those of us who bring a second wave feminist experience of consciousness-raising to our study of the 19th century reformers can easily imagine Rose and Wright Davis strengthening one another through sharing of life experiences. Both women suffered grievous losses in the early years of their collaboration. Rose lost two infant children in the 1840s, and Wright Davis lost her first husband, Francis Wright, who died in 1845. It is hard for us to imagine two women working so closely on issues that directly affected their lives, and not talking about important events in their own lives. On the other hand, both women were famously reticent about personal matters, were working at opposite ends of the state, probably rarely meeting in person, and may have been inhibited by the etiquette of a more formal time. Whether or not these two were close friends, their association and collaboration as reformers was a bond that lasted for nearly four decades. Both women made early and outstanding contributions to the rights of women.

Despite their visionary, vigorous, and continuing participation in the first wave of feminism, these two women, Ernestine L. Potowski Rose and Paulina Wright Davis are virtually forgotten today. Often, as movements become institutionalized, the visionaries are forgotten. Yet it is important to remember them, honor them, and learn from them. When we study the growth and development of social movements, we must not overlook those who initiated progressive activism before it was socially acceptable. In the words of Ernestine Rose’s toast to reformers, “Let us by honoring the memory of reformers in the past, and by aiding the efforts of those in the present, encourage the rise of others in future time.”—At the Thomas Paine Birthday Commemoration in New York, 1840.

About The Author

Paula B. Doress-Worters, Ph.D. is a Resident Scholar in the Women’s Studies Program at Brandeis University, where she is working on a fictionalized memoir of Ernestine Rose, and is Founder and Director of the Ernestine Rose Society. Doress-Worters is a Founder of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, co-authors of Our Bodies, Ourselves (for the New Century), and is co-author of The New Ourselves Growing Older. Paula will be a part of the panel, “A Women’s Health Perspective: Where We Have Been and Where We Are Going” at Women 2000.

Selected Bibliography

Anderson, Bonnie. Joyous Greetings: The First International Women’s Movement, 1832–60. New York, Harper-Collins, 2000. Includes material on Rose and Wright Davis along with many others.

Kolmerten, Carol A. The American Life of Ernestine L. Rose. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1999. Includes most extensive documentation on Rose.

Suhl, Yuri. Ernestine L. Rose: Women’s Rights Pioneer. New York: Biblio Press, 1990. Introduction and Preface by Rosalind Fraad Baxandall and Francoise Basch. Includes excerpts from Rose’s speeches.

Tonn, Mari Boor. “ The Una, 1853–55: The Premiere of the Woman’s Rights Pressin Martha M. Solomon, ed., A Voice of Their Own: The Woman Suffrage Press, 1840-1910. Tuscaloosa and London: Univ. of Alabama Press, 1991, pp. 48-70.

From: Archives of Rhode Island Historical Society: Amy L. Nathan, Paulina Wright Davis: Senior Honors Thesis, Brown University (under direction of Mary Jo Buhle) Dept. of History, 1977; Constitution and Book of Minutes of the Providence Physiological Society (1850).

From Vassar College Libraries: Collected lectures of Paulina Wright Davis.

Author’s Note

On a 1998 visit to Highgate Cemetery in London, I was appalled to discover that Ernestine Rose was not featured on the list of Eminent Persons distributed to visitors to Highgate, and that there was no stone marking where Ernestine and William Rose were buried. An employee of the cemetery agreed to carry out a search for their plots and reported that the original small stone had sunk into the ground. In correspondence with the Trustees of Highgate, I successfully appealed to add Rose’s name to their list of Eminent Persons which includes such notables as Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), Karl Marx, and George Jacob Holyoake. I have since founded the Ernestine Rose Society to honor Rose’s legacy and to raise funds to restore the sunken marker. For information, write to me at Brandeis University, Women’s Studies Program, or e-mail to pdoress@ mail2.gis.net. Or look for me at the October conference. I will have the Society brochures to hand out.

Photographic Credits

Photographs of Ernestine L. Rose and Paulina Wright Davis, courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

Happy Birthday Dear Lucy

On Sunday, August 13, from 3:00 to 4:30 p.m., WWHP, in conjunction with the Quaboag Historical Society, sponsored a birthday party for Lucy Stone in her hometown of West Brookfield.

On Sunday, August 13, from 3:00 to 4:30 p.m., WWHP, in conjunction with the Quaboag Historical Society, sponsored a birthday party for Lucy Stone in her hometown of West Brookfield.

Lucy Stone (1818–1893), the subject of one of the four new portraits added to Mechanics Hall last year, was one of the most influential women in America. She was one of the first women from Massachusetts to earn a baccalaureate degree, the first to speak publicly on behalf of women’s rights, and the first American woman to retain her birth name after marriage. She was also a teacher, writer, and editor, a tireless advocate for equality, a founder of the American Woman Suffrage Association, and one of the organizers of the National Woman’s Rights Convention in Worcester in 1850.

Almost 100 people attended the birthday party, which was held in the historic Great Hall at the West Brookfield Town Hall. Distinguished guests included Carolyn Howe, President, and Lisa Connelly Cook, Co-Founder, of WWHP; William Earley, President, and Marguerite Geis, Secretary, of the Quaboag Historical Society; Constance Small and Paul Walker, 1999 and 2000 winners, respectively, of the Lucy Stone Award for Community Service; Barbara Rossman, representing the West Brookfield Historical Commission; Johanna Barry, representing the Selectmen’s Office of West Brookfield; Anita Aspen and Connie Riley, representing the Lucy Stone Commemorative Committee of Gardner; Helen Whall, representing the Lucy Stone League; State Senator Stephen M. Brewer; and retired State Senator Robert Wetmore, who initiated the successful proposal to have March 8th designated as Lucy Stone Day in the Commonwealth.

Folksingers Chuck & Mud presented a wonderful concert that featured the premiere of a new song based upon a poem written for Lucy by her daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell.

After the first half of the concert, some of the distinguished guests spoke about Lucy’s life and legacy. These speeches culminated in the reading of a proclamation, authored by State Representative David Tuttle, which commended the WWHP and the Quaboag Historical Society for celebrating Lucy’s birthday. An enormous cake—decorated in teal and lavender, the WWHP colors—was presented to “Lucy Stone” and to Sen. Wetmore. After blowing out the candles, Lucy, portrayed by Anne Earley, said she had wished, once more, that “women might someday achieve full equality with men.”

Other activities included Andi the Clown, who did face painting and made balloon animals for children; and tables featuring many items for sale from the Lucy Stone League, the Quaboag Historical Society, the Unitarian-Universalist Woman’s Heritage Society, and WWHP.

The party was organized by Nancy Avila and Beth Sweeney, of the Marketing Committee, and Marguerite Geis, of the Quaboag Historical Society. The organizers are especially grateful to the Common Committee, the Selectmen’s Office, and Sacred Heart Church in West Brookfield; the Lucy Stone League; Catered by Adams, of Spencer, who donated paper napkins, plates and cutlery; and Lorraine Starr, who designed the invitations for special guests. Marj Connelly, Laura Howie, David L. Smith, Connie White, and Kelsey White helped immensely at the event itself.

The Outreach and Marketing Committees feel the party was a tremendous success, especially considering the damp weather that day. One of the goals was to reach out to the western suburbs and strengthen our ties to local historical societies. We were very pleased, therefore, with the good attendance, the positive relationship that we developed with the Quaboag Historical Society and other groups, and the coverage we received in the Springfield Union News, the Ware River News, and the Spencer New Leader.

Lodgings Needed

WWHP seeks people who wish to offer overnight and/or weekend lodging in their homes to people attending Women 2000. If you’re interested, please contact Marty Flint at 754-1467.

Attention Volunteers

Volunteers for Women 2000; please call Sandra Macintyre at 753-6300.